Selecting the optimal refrigerant is a complex decision that varies significantly by application, as each option presents distinct advantages and tradeoffs. Key factors must be evaluated within the context of your specific system requirements and operating conditions to determine the most suitable choice.

Too often, limited analysis results in oversimplified judgments – declaring one refrigerant as the universal best choice while dismissing all alternatives. The reality is more nuanced, requiring a comprehensive evaluation of several key factors, which we will explore in detail below.

1. Efficiency: Beyond Simple Metrics

Energy efficiency in refrigeration systems presents a complex interplay of factors. Energy usage varies significantly based on application, refrigerant choice, and system design. An efficient refrigerant in one project may not be so efficient in another.

Refrigerant properties: In a vapor compression refrigeration cycle the compressor functions as the system's heart, circulating refrigerant and driving the entire process. To accomplish this, most refrigerants leverage phase change – the transition between liquid and vapor states – to facilitate heat absorption and rejection. Within this fundamental process, refrigerants exhibit vastly different physical properties that significantly influence system performance.

Key physical properties create distinct performance characteristics. For example, a refrigerant with high latent heat of vaporization (how much heat is absorbed when boiling) requires less circulation to achieve the same cooling effect. Higher-density refrigerants allow the use of smaller compressors and can improve heat transfer in heat exchangers. A refrigerant with a lower boiling point at a given pressure can be used at lower temperatures. These are just three examples.

The way these properties interact in a system affects another factor, for any given refrigerant and set of operating temperatures, there is a maximum theoretical coefficient of performance (COP). Ammonia (NH3) has established itself as the efficiency benchmark among refrigerants, generally outperforming other refrigerants across diverse operating conditions. This superior performance explains its prevalence in large-scale food processing and other industrial-sized cooling applications.

System design: System design plays a crucial role in optimizing efficiency. Performance improvements can be achieved through various engineering approaches, such as implementing heat exchangers with closer approach temperatures, minimizing refrigerant pressure drops, employing multi-stage compression or economizing, the type of compressor, and even motor cooling means. However, the effectiveness of these design strategies varies depending on the refrigerant choice, as these measures are not equally effective with different refrigerants.

2. Safety: A Primary Consideration

While the ideal scenario is for refrigerants to remain sealed within their systems throughout their operational life, leaks can and do occur. This reality demands a thorough evaluation of each refrigerant's safety profile, potential risks, and necessary mitigation measures for specific applications.

Toxicity: Claims that a refrigerant is either "non-toxic" or "toxic" oversimplify a complex issue. Most refrigerants carry some degree of toxicity. Air can function as a refrigerant and is a rare exception, though its use is limited (due to other factors) to specialized applications like aircraft cabin cooling.

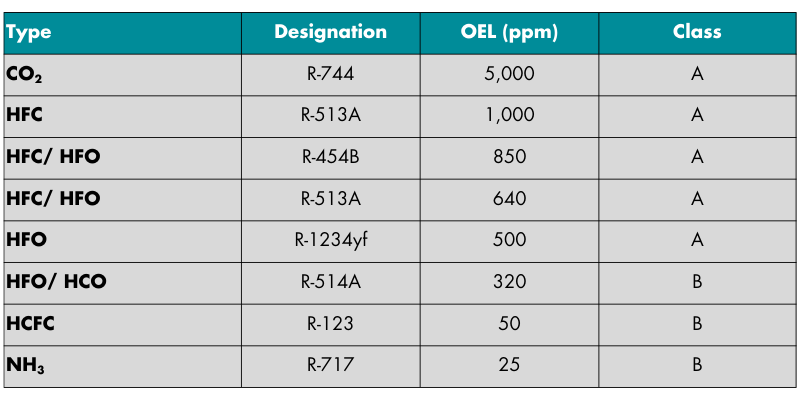

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) assesses refrigerant toxicity in Standard 34 – Designation and Safety Classification of Refrigerants. This framework categorizes refrigerants into two classes based on their occupancy exposure limit (OEL):

- Class A: "Lower toxicity"

- Class B: "Higher toxicity"

(The threshold between these classifications is set at 400 ppm.)

Here is the toxicity classification of several refrigerants, as per ASHRAE

If the quantity of refrigerant in a system is sufficient that the toxicity or flammability concentrations can exceed the acceptable limits, then the ability to detect a leak is crucial. Most refrigerants are odorless, which presents a safety risk, but ammonia (NH3) has a unique advantage as a self-alarming refrigerant due to its sharp, irritating, and pungent odor. With an average odor threshold of 5 ppm, well below harmful concentrations, ammonia's distinctive smell ensures that even small leaks are quickly detected and repaired.

Flammability: Much like toxicity claims, declarations of "non-flammable" refrigerants can be misleading. Carbon dioxide (R-744) is a notable exception – not only does it not burn, but it also acts as a fire suppressant when released near flames.

ASHRAE Standard 34 provides a systematic classification of refrigerants based on their flame propagation properties, tested under specific conditions at a temperature of 140 °F (60 °C) and a pressure of 14.7 psia (101.3 kPa).

Most current air-conditioning refrigerants fall into Class 1, designated as "No Flame Propagation." However, this classification has an important caveat: Many Class 1 refrigerants can become flame-propagating at higher temperatures and pressures. More concerning is that when exposed to flames, many can decompose into highly toxic substances, including chlorine, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, phosgene, and carbonyl fluoride.

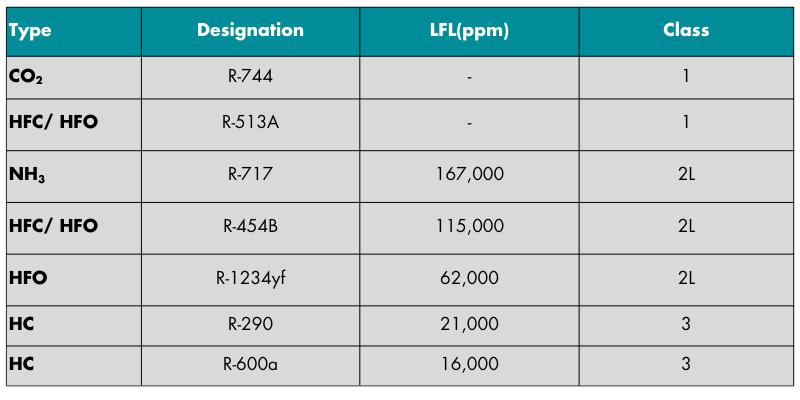

ASHRAE Standard 34 establishes three additional classifications for flame-propagating refrigerants: Class 2L for “lower flammability,” Class 2 for “flammable,” and Class 3 for “higher flammability.”

The ASHRAE standard also includes the Lower Flammability Limit (LFL), the minimum concentration in air required for flammability. However, this measurement is included for reference only, as it does not affect classification.

Critical reminder: The designation "non-flame propagating" should not be confused with "non-flammable" or "non-combustible."

Here are the safety classes as per ASHRAE of some commonly used refrigerants

Installation: Comprehensive safety standards restrict when and how a refrigerant can be used in a system as well as the necessary safety requirements to ensure safe operation. Evaluating these restrictions and requirements is essential when making a refrigerant decision. In the United States, ASHRAE Standard 15 Safety Standard for Refrigeration Systems is the widely adopted framework for most refrigerant installations. In comparison, ANSI/IIAR 2 American National Standard for Design of Safe Closed-Circuit Ammonia Refrigeration Systems applies for ammonia (NH3, R-717). In Canada, CSA B52 Mechanical Refrigeration Code is adopted for all refrigerants except water and air.

3. Environmental Impact: A Complex Balance

The relationship between safety and environmental impact presents an unexpected paradox: refrigerants with lower immediate safety risks often carry more significant long-term environmental consequences. This reality demands evaluation across several critical environmental factors.

Ozone Depleting Potential (ODP): The 1990s marked a turning point with the phase-out of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) refrigerants due to their high ODP when released into the atmosphere. Eventually Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) faced the same fate. While current regulations prohibit new systems from using refrigerants with any ODP, this introduced new environmental challenges.

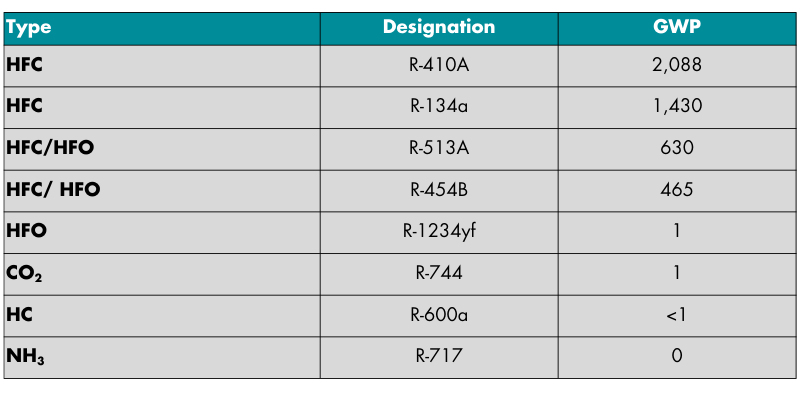

Global Warming Potential (GWP): The hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants that replaced CFCs and HCFCs revealed an unexpected drawback: When they leak into the atmosphere, they act as global warming agents, typically thousands of times more potent than Carbon Dioxide.

Recent developments have introduced refrigerant blends combining HFCs with mildly flammable Hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) to reduce GWP while maintaining the non-flame-propagating Class 1 status. These blends are frequently marketed as "low" GWP refrigerants; however, with GWP ratings between 600 and 1,400, they are far from a low-GWP solution.

Even newer HFC-HFO blends classified as mildly flammable 2L refrigerants represent progress, but they still demonstrate GWP ratings hundreds of times higher than CO2.

In contrast, natural refrigerants have emerged as environmental leaders: NH3 with GWP=0, CO2 with GWP=1 (the benchmark), and hydrocarbons with GWP=3

Source: Technology Transitions GWP Reference Table | US EPA

Contamination: When certain HFC and HFO refrigerants leak into the atmosphere, they break down and produce trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), a "Forever Chemical" that persists for thousands of years. The accumulation of TFA raises growing concerns about long-term environmental and health impacts on ecosystems and living organisms.

Production and disposal: The environmental impact of refrigerants extends throughout their lifecycle.

Energy requirements for production and disposal vary significantly among refrigerants. CO2 stands out favorably in this regard, as it is a byproduct from other industrial processes, requiring minimal additional energy input.

Historically, Manufacturing processes have witnessed chemical releases and exposure incidents, with some chemicals used during the production of fluorinated refrigerants posing even greater concerns than the refrigerants themselves.

4. Cost and Availability: Scale Matters

The impact of refrigerant costs varies dramatically with system size. In residential or commercial air-conditioning systems, where refrigerant charges are relatively small, the cost of recharging after a leak remains manageable. However, the equation changes significantly for larger commercial and industrial refrigeration systems, which can contain hundreds or thousands of pounds of refrigerant.

While modern system design has reduced typical refrigerant charges, these larger systems present unique challenges. Their complexity – often incorporating hundreds of components and thousands of feet of pipe – increases leak potential. This risk is particularly concerning with odorless refrigerants, where small leaks can result in significant losses before detection.

The cost differential between refrigerant types adds another layer of consideration. Fluorinated refrigerants (F-gases) typically cost dozens of times more than natural alternatives like NH3 and CO2. Historical trends have shown that as older fluorinated refrigerants (f-gasses) face regulatory phase-outs or chemical manufacturers cease production, costs escalate sharply as availability becomes increasingly uncertain.

Conclusion: Making the Right Choice

No single refrigerant is perfect for all situations. Selecting the best refrigerant requires careful consideration of safety requirements, environmental impacts, system efficiency, costs, and availability.

With constantly evolving refrigerant regulations and rapidly advancing technology, staying updated with the available refrigerants and their properties is crucial to making the right choice for each individual project.

Wayne Borrowman– Director, Research and Development

Wayne is a highly experienced refrigeration engineer and subject matter expert, boasting an impressive 37 years of experience in the field. Since 1988, he has been with CIMCO Refrigeration, where he has held various progressing engineering roles focused on design, engineering, and project management of over 500 refrigeration projects. In addition, Wayne is responsible for the research and development of new products and solutions in thermal management.

Wayne's vast experience, industry involvement, and expertise make him an invaluable asset to the HVAC and refrigeration engineering field as a whole. His contributions to the industry have been significant, and his expertise is highly sought after by peers and colleagues alike.

Email: wborrowman@toromont.com

Related Posts

Navigating HFC Regulations: Federal and State Initiatives to Reduce Global Warming Potential

Decarbonizing Food Processes with Industrial Heat Pumps

Interconnected Efficiency: Leveraging Ammonia Heat Pumps for Sustainable Manufacturing

STAY UP TO DATE

Get the latest industry insights and important updates delivered right to your inbox.

|

|